The Importance of Subsistence and Sedentary Societies in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is composed of two vastly different societies that have been historically difficult to reconcile, let alone control under a unifying banner.

With the U.S military intervention in Afghanistan concluded, much was made about the many missteps along the way. The most notable report being The Afghanistan Papers1 which document the disarray within the U.S government in its handling of the war. In the West, the news cycle will eventually fade this event into history, only to be brought up during election cycles as a partisan talking point. It is as if this was a fleeting moment in history, much like a mid-season baseball game, and not one which changed the future of generations of Afghans to come. The learnings from the endeavour were more reinforced than discovered, as the strategy of exporting western democracy as if it is a readymade antidote which needs only to be consumed by a willing patient, is inherently flawed. It hints at both hubris and a lack of understanding of Afghanistan’s people, landscape and history. This post will focus one one idea which contributes heavily to this misunderstanding of the region, and is a constant throughout Afghanistan’s history dating back to the 9th and 10th centuries when present day Afghanistan was more widely known as Turko-Persia. That idea is the differences between the region’s subsistence society and sedentary society.

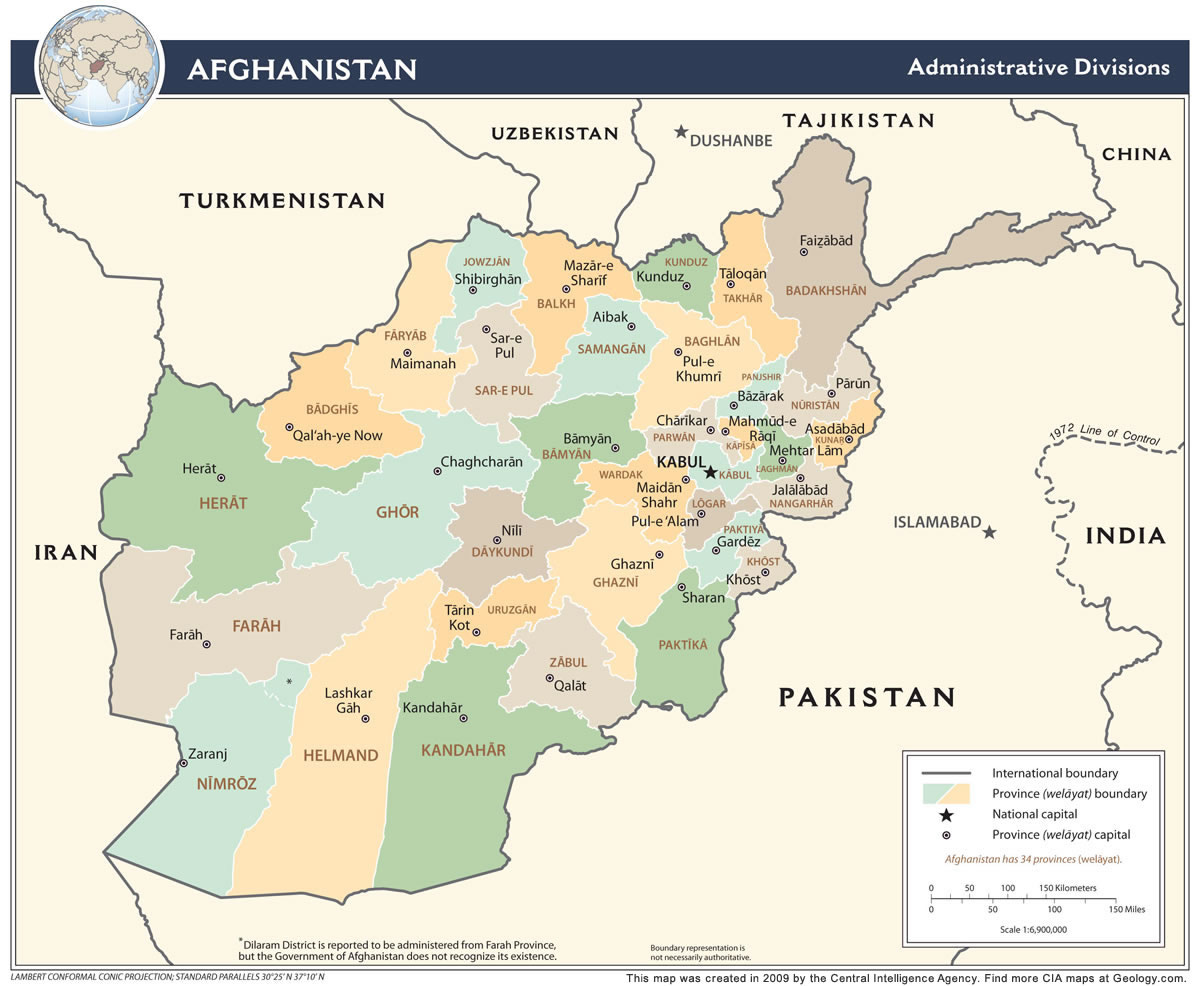

It is much more accurate to use the word region instead of country because much like post-colonial Africa, Afghanistan’s geographic borders are not reflective of a group that could be considered homogenous in many respects, let alone ethnicity or culture. To the south and east, Afghanistan borders Pakistan with the Durand Line (a remnant of English colonialism from 1919) serving as the official border. This line divides the Pashtun ethnic group living in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and is widely rejected by them with border crossings resembling how one would cross a state line in the United States. This border for containment purposes is meaningless.

The borders are important because Pakistan, the main western ally in the region, has little to no control over Afghanistan, and to rely on it as a proxy for western intervention is like asking your five-year old to babysit your teenager. The teenager will come and go as they please and do what they like. It isn’t the five-year old’s fault, it’s the parents fault. On the east there’s Iran and on the north, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan with a sliver of the north-eastern part bordering China. None of these countries are sympathetic to western interests. This geography means that there must be strong support and inclination internally within Afghanistan to instill any sort of political change. To rely on interventions via regional influences is a dubious strategy, complicating an already daunting change effort.

If one is to understand Afghanistan they must start with the two dominant ways of living in the country. First, subsistence societies. These are tribal and nomadic societies which only produce what they consume. They live in the steppes, villages and mountainous regions away from the main centers of Kabul (east), Kandahar (south), Herat (west) and Mazar-i-Sharif (north). They are organized in groups ranging to a maximum of 10,000 people, and follow an egalitarian way of life2. Unlike modern societies which tend to be hierarchical in order to make decision-making and control easier, these societies are flat and make consensus-based decisions. Their concerns are limited to the happenings within their group, and though they rely on other groups for economic purposes such as trade, they are socially isolated by design. They are extremely intra-dependent for subsistence and security, and require high communication within the group to survive. Though they have conflicts within the group, they are a single entity when facing outside threat.

This is best summarized by an old Bedouin proverb, “Me against my brother, my brother and I against my cousin, and all of us against the stranger.”

Any surplus production by the group is not exported but distributed within to elevate one’s social status (not to be confused with political status or power). These groups have historically cared little for who is in charge in the central cities, especially in the capital city of Kabul. It is not that they don’t recognize who is in power in Kabul, but it impacts them so little that they simply don’t care, what with the daily grind consuming their existence. Their leadership comes not from federal or provincial governments, but from within the group with the leader being a “first amongst equals”, an old tribal concept made most famous by the Arabs and Prophet Muhammad. In fact, they tend to have their discussions in circles specifically to avoid even a hint of a hierarchical structure.

Historically when central governments were weak, these groups sensed an opportunity and took control of the country, so despite their subsistence lifestyle, they should not be considered militarily weak. It is also worth nothing that since the inception of Turko-Persia in the 9th and 10th centuries (present day Afghanistan), rulers did not often bother controlling or administering these societies due to the terrain, seasonality and the cost of administration. They were simply left alone because it wasn’t worth it.

The leadership in these societies was not hereditary as both tribes and nomads despise the idea of bloodline dictating leadership rights. Anyone in the group could become the leader if they had the right skills in building consensus and enough social capital, making tribal affairs often a heated matter and leadership turnover high.

The second type of society is what is generally termed sedentary societies. Unlike, subsistence societies, they produce an economic surplus which results in division of labour, i.e., different parts of a production process are assigned to different people in order to improve efficiency. This is a stark contrast with subsistence societies which contain the whole “value chain”. These are societies that are similar in nature to Western ones, where people are heavily dependent on each other, but have little reason to communicate. They are more educated, more worldly, and more prone to manipulation as they are heavily interwoven into communication channels (in modern times, mass media and in olden days, the silk routes). They have also historically been the dominant rulers of the country.

It is important to note that whether it be the Mongols from the north or the Turks from the West, or an internal challenger to power, wars for Afghanistan should always be seen as rulers fighting other rulers for economic, logistical and geographic control (usually access to India). It is an error in analysis to view these wars through an ideological or religious lense, like the West has recently done in trying to export democracy. These wars were never about how the general population lived their day-to-day lives, what political system they followed or which god they worshipped.

The majority of the population base resides in the city centers and thus in sedentary societies, but these have increasingly relied in migration from the villages for people looking for work. Thus, one will find cities filled with the major ethnic groups like the Balochis, Pashtuns, Tajiks, Turkmens, Hazaras and others. Though these ethnic groups have different cultures and religious sects, once they move to the cities, they become more like each other than not. This is much different than subsistence societies where even though two groups may be geographic neighbors, they would not exhibit the same level of trust between themselves and would often exhibit tensions.

Prior to 1973 when the monarchy was abolished, leadership in sedentary societies was hereditary constituting a core disagreement on how the power structures in the two societies were organized. From the perspective of subsistence societies, this was an unthinkable way of picking leadership but as long as interference from provincial centers was low, it could be ignored. Five years later in 1978 the Soviet invasion occupation began. This ended in 1989 which started an era of foreign interference which lasted till 1996, which is when the Taliban took over the region. Throughout Afghanistan’s history, there has never been a leadership model which administers strong control over both subsistence and sedentary societies.

Though the two societies are dependent on each other, often transitively, for economic purposes (for example, the salt that is used to feed cattle in nomadic areas comes via trade from cities), they cannot be further apart when it comes to aligning on where power should reside. And certainly subsistence societies would resent being told what kind of political system to follow for decision-making as for them the tribe is the all-encompassing decision-making system. The idea of “foreign relations” for someone in a city is vastly different than someone in the village. In the village they couldn’t care less about what kind of a terrorist threat Al-Qaeda might be to the U.S, but that could very well be a reasonable talking point in Herat or Kabul. Sedentary societies value integration with the rest of the world more because they seek efficiency, choice variety and are motivated by economic surplus. Sedentary societies laugh at economic surplus gained through foreign trade. For them, foreign is the tribe next door.

These differences are also ancient. Though a popular phrase, it is simply incorrect to call Afghanistan the Graveyard of Empires. It was ruled up until 1738 by the Timurids, Safavids, Mughals, Uzbeks, and Hotakis, which is when Nader Shah took over followed by Durrani rule. Throughout this time this dichotomy between subsistence and sedentary societies remained intact, with most rulers giving the people at the margins, more or less, full autonomy as long as the taxes were paid (where the terrain and weather allowed). The tension between the two was ever-present and relations opportunistic more than socially motivated.

It is in this context that one must view the mission of spreading Western Democracy to Afghanistan. It is not so much that Afghanistan is a Graveyard of Empires, it is a graveyard of wholesale ideologies. It is a country whose borders are meaningless (the Pakistan side was discussed earlier but the same applies to the north), its cultures fragmented and physically distant, its terrain harsh, and its roads minimal (5 km/100 km squared, 12th worst in the world3). Centralized control of anything in a country like this has proven to be impossible, with decentralization and autonomy being the only viable option.

Without central control, the people at the margins are free to do what suits their group the best. There is no desire or benefit to subscribe to Western Democracy for four reasons:

its infeasible to implement

it offers no tangible benefit in their context

they are familiar with a system which has served them for more than a thousand years

it is resented, not because it is from the U.S but because it comes from the city centers of Afghanistan, whose leadership models are resented

It is this tension between subsistence and sedentary societies, or more generally, rural and urban populations which leaves the door ajar for local intervention by the Taliban.

This is best documented in Gilles Dorronosoro's comprehensive report, The Taliban's Winning Strategy4, which covers the situation in detail, but also focuses on this inherent tension and how the Taliban leverages it.

The Taliban propaganda builds on the widely perceived corruption of the Afghan government, the lack of basic services for the people, and the historical narrative of the fight against infidel invaders (British, Soviets, and Americans). Less overtly, the Taliban also play on rural people’s distrust for cities, which are seen as corrupted and corrupting.

The Taliban’s main tool for leveraging this distrust is to gain influence and control by crossing tribal boundaries through their appointment of mullahs (i.e., religious leaders) as authority figures. Instead of gaining each tribe’s support, their strategy of calling to a divine authority to gain control is an effective one, especially once backed by the fear of violence. The mullah speaks to all tribes and nomads, regardless of ethnicity or geography, thus supplying a unifying message crossing tribal structures, which when coupled with powerful communication mediums, amplify their message.

However, religion, the provisioning of social services, disinformation are just tools in exploiting the rift that exist between the two societies. They are catalysts exploiting a historic divide.

The U.S strategy of reconciling the two societies in order to gain their support was through nation-building, specifically the building of infrastructure which all Afghans could benefit from and which would hopefully lay the foundation of trust in a centralized government. Though a reasonable strategy on paper, the execution of this was a failure5.

Callen and others blamed an array of mistakes committed again and again over 18 years — haphazard planning, misguided policies, bureaucratic feuding. Many said the overall nation-building strategy was further undermined by hubris, impatience, ignorance and a belief that money can fix anything.

Much of the money, they said, ended up in the pockets of overpriced contractors or corrupt Afghan officials, while U.S.-financed schools, clinics and roads fell into disrepair, if they were built at all.

Some said the outcome was foreseeable. They cited the U.S. track record of military interventions in other countries — Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Haiti, Somalia — over the past quarter-century.

“We just don’t have a post-conflict stabilization model that works,” Stephen Hadley, who served as White House national security adviser under Bush, told government interviewers. “Every time we have one of these things, it is a pickup game. I don’t have any confidence that if we did it again, we would do any better.”

To conclude, the inability of NATO forces and the Afghan government to connect two vastly different societies under a common umbrella, coupled with the fractures within subsistence societies, always left the door open for the opportunistic and patient Taliban.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/sep/05/the-afghanistan-papers-review-craig-whitlock-washington-post

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7718203-afghanistan

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/roadways/country-comparison

https://carnegieendowment.org/files/taliban_winning_strategy.pdf

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-nation-building/